This article was originally published on the New Internationalist website on 4 July 2018.

Like many Palestinian families in East Jerusalem, the Sumarin family is facing eviction under a controversial Israeli law. Amy Hall reports

Every year, Wardeh and Ahmad Sumarin watch as more of their neighbours are evicted, their homes sold on to become houses for settlers.

The Sumarin family’s home is in the Wadi Hilweh neighbourhood, at the entrance to Silwan in East Jerusalem. It is a highly contested area: just south of the Old City walls, at the foot of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites. It is also the location of the City of David, believed the site of the biblical city of Jerusalem.

The predominantly Palestinian community of Silwan is a focus for Jewish settlement, aided by Israel’s Absentees’ Property Law. In 1967, Israel illegally annexed thousands of hectares of West Bank land into the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem and applied Israeli law to it.

Palestinians living there were given the status of ‘permanent resident’, effectively becoming second class citizens. In June that year, Israel held a census in the annexed area – East Jerusalem – and any Palestinians who happened to be absent at the time (including those displaced by the occupying conflict), lost their right to return to their home.

Many Palestinian families who have been evicted under this law did not even know that their homes had been declared ‘absentee’ property and sold on until legal proceedings were initiated against them to evict them.

The extended Sumarin family – 13 people, including six children – are now facing homelessness thanks to this law. In 1991 a land deal was signed between the authorities and Himnuta, a subsidiary of the Jewish National Fund (JNF), an organization with close links to the Israeli state which owns a significant percentage of Israel’s land. Himnuta has been trying to evict the family ever since.

Since the early 1990s some of the properties acquired under this deal have been leased to the Israeli NGO Elad, which promotes Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem, and Jewish settlers have been moved in. According to human rights group B’Tselem, since the 1990s Elad, and other organizations, have moved 60 Jewish settler families – around 300 people – into the neighbourhood of Wadi Hilweh.

Ahmad says that Musa – the uncle of his grandfather – built their house in 1950. Musa’s sons were in Jordan in 1967 to escape the war. Ahmad says his grandfather and father lived in the house with Musa and that his grandfather bought it from Musa in 1981: ‘After he died Himnuta said that my grandfather and dad weren’t from the family and they said that it was their house.’ The house was declared ‘absentee property’.

‘There are so many families with the same problem,’ says Wardeh. ‘Every year settlers take more houses under the same law. Israel’s law protects them and lets them take any house they want.’ Standing on the flat roof of the Sumarins’ home the Israeli flags flying above occupied houses are clear to see.

The Sumarin family live right next to the Al-Aqsa Mosque

Will the family receive any compensation for leaving their home?

No. Himnuta wants them to pay for the privilege and has included in its legal claim a demand for the family to pay NIS 500,000 (Israeli New Shekels, equal to $137,000) for having stayed so many years on the land.

‘They say if you don’t pay they’ll take everything you have,’ says Wardeh.

Since 1967, hundreds of the family’s neighbours have been ordered to pay fines ranging from thousands to tens of thousands of shekels (3.5 shekels equals 1US$).

The JNF receives donations from people around the world. It was formed in 1901 to buy and develop land in Palestine for Jewish settlement. There is an international campaign against the organization’s role in occupation and apartheid, which also targets JNF organizations around the world, including the UK branch of the organization.

In December 2011, a JNF-USA Board member, Seth Morrison, publicly resigned in protest over the Sumarins’ case, while pointing out that they were not the only family under threat. ‘JNF has gained ownership of other Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem and, in many instances, then transferred these properties through its subsidiaries to Elad, a settler organization whose purpose is to “Judaize” East Jerusalem,’ he wrote at the time.

The Sumarin family would like people outside of Israel to put more pressure on the JNF. ‘People in Europe think that they give money to the JNF to plant trees, or to help poor people – for something good – but they don’t know that they take the money and use it to pay lawyers and take people’s houses,’ says Wardeh.

The Sumarins’ story is, in many ways, a familiar one. In 2017 alone, 86 homes in East Jerusalem were demolished – 10 in Silwan. 155 people were left homeless.

Amit Gilutz, a spokesperson for B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, explains that there is a massive imbalance in the allocation of public resources for Palestinian neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem, including health care provision. These communities are also severely restricted in terms of construction and development. ‘Israeli policy in occupied East Jerusalem is meant to drive Palestinians out of the city,’ he says. ‘It makes people seem like unwelcome visitors in their own homes.’

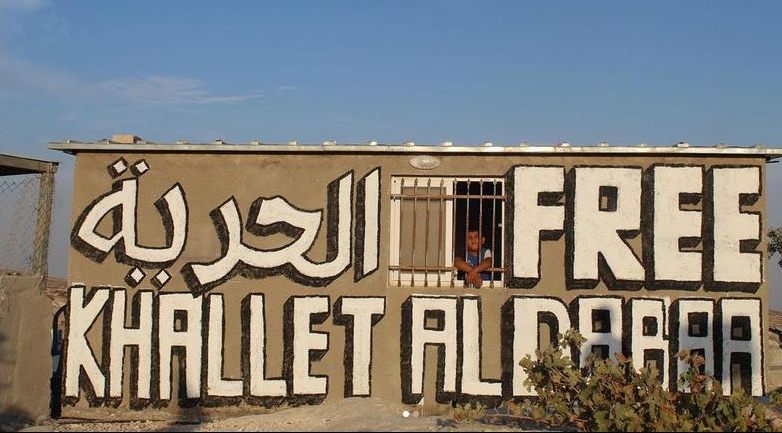

Many of the family’s neighbours have been forced out, their homes taken over by settlers.

Palestinians in Silwan are increasingly made to live in close proximity to ideologically extreme settlers, who usually come with armed security, and sometimes violently harrass Palestinians. Many of the houses surrounding the Sumarins have been occupied by settlers who have security guards with guns – ‘the security guards go everywhere with them,’ says Wardeh.

Gilutz explains that National Parks – like the Jerusalem Walls National Park, which includes the City of David – are part of the strategy of limiting the land available to Palestinians. Four national parks have been declared in East Jerusalem, including on privately owned Palestinian land. Wadi Hilweh – home to around 4,000 people – is almost completely inside the Jerusalem Walls National Park and the City of David is at its centre.

The City of David site has brought with it massive restrictions on the open space accessible by residents. There are traffic jams, an increased amount of security personnel, including soldiers, and surveillance cameras.

The visitor’s centre for the site, which Elad is constantly trying to expand, right next door to the Sumarins’ home, is operated by Elad – which also funds excavations in various parts of the neighbourhood. Hundreds of tourists pour into the neighbourhood each day, cramming people, buses and taxis into the narrow streets.

International pressure has already delayed the Sumarins’ eviction by several years, and the family are hoping the same can happen now – or even better that it is thrown out altogether. They are expecting a final court decision on their case in the autumn.

Wardeh’s family also live just down the road, and the Sumarins don’t know what they will do if they are forced to leave.

‘We can’t imagine where we’ll go,’ says Wardeh. ‘We were born here, our family is here. Our work, children and school are here.

‘I can’t tell you what we’ll do because my life is in Silwan.’

0 Comments