By Amy Hall. Many thanks to Eliza Egret, Lydia Noon and Tom Anderson for their help with the interview.

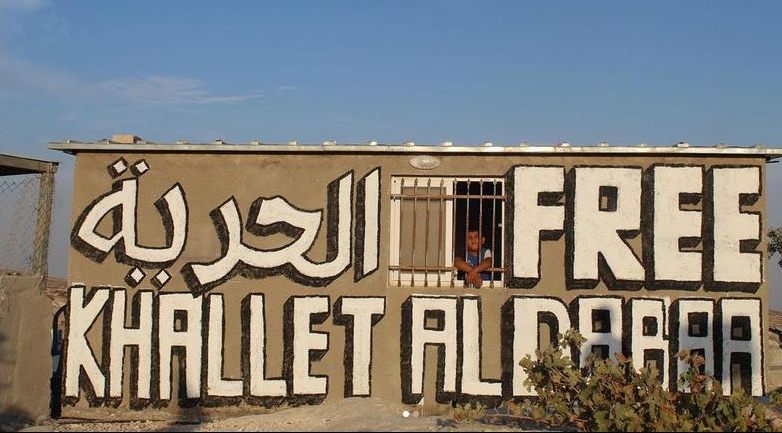

This is part of a series of interviews with Palestinians from Area C who have experienced demolitions of their homes or property carried out by the Israeli occupation authorities. In our interviews we will show some of the effects of demolitions, and highlight the companies involved in carrying them out.

Some of Rezeq Abu Nasser’s most vivid memories are of Wadi Qana – the lush valley next door to his home village of Deir Istiya. Here was where he first learned to swim without help, where he and his brother almost got struck by lightning in a freak storm during an olive harvest. Rezeq spent over two years in the Wadi in the late 1980s, hiding from the Israeli authorities, one day narrowly escaping arrest by climbing a tree, within earshot of the army.

Central to all these memories is the small house passed down through his family, who have been coming to the Wadi to farm their patch of land, grow olives and raise goats for generations. That house is now a shell. The base of a few of the crumbling walls is all that remains after it was destroyed by the Israeli army.

On 12 February 2018, the soldiers arrived at around 7.00am. By chance, 58-year-old Rezeq was already there. He saw around 30 border police and soldiers, as well as workers from the Civil Administration and the Nature Reserves and National Parks Unit.

The remains of Rezeq’s house

Rezeq couldn’t contain his anger. “The soldiers said that I was only claiming to own the land, that I was lying” he explains. “I said ‘Go ahead and shoot me. This is my land, these are my goats.’ I couldn’t stay near the soldiers as I was too angry.

“They said to me in Hebrew that I had five minutes. I lit a cigarette, but they said I would be arrested after five minutes and that I should collect my things and that this was not a time for smoking.

“I didn’t have time to collect all of my things. I would have needed at least five trips to get our mattresses and everything else. I only collected cigarettes, some lights, chargers, batteries, some dishes. I was confused and just collected what I saw.

“The other things that I didn’t have time to collect, some got taken by the workers [from the Israeli Civil Administration], some were destroyed. I never got my things back.”

Rezeq says that the machine used to destroy the house was made by the British company JCB, one of the world’s top three manufacturers of construction equipment.

In November 2017, Rezeq’s family had received a demolition order from the Israeli authorities. The reason? They had put a tarpaulin on the roof and some extra stones in a wall to plug the gaps. They had also put some cement on the ground to try and level out the floor.

The house is in Area C. Here Israel has full control and it is almost impossible for Palestinians to get permits to do any type of building work, including renovations.

The Wadi was declared a nature reserve in 1983 by the Nature Reserves and National Parks Unit of the Israeli Civil Administration. It had previously been declared a closed military zone in 1978. Both are recognisable tactics used by Israel to block Palestinian development in Area C.

Now, Rezeq explains Palestinians in Wadi Qana cannot even plant trees. In fact, Rezeq had his trees destroyed by the Israeli authorities several times. Between 2015 and 2017 he says they uprooted more than 3,000 plants and saplings, a lot of them olive trees.

“But we can still take care of what we have,” he says, showing us lemon trees that were planted in the 1960s.

Wadi Qana is used as a place for people to come and have picnics, relax or do small scale farming

The area is mostly used for leisure by Palestinians, but Rezeq says they are not allowed on the land after 8.00pm.

Wadi Qana is now overshadowed by Israeli settlements, established between 1978 and 1986, on the hills overlooking both banks: Immanuel and Karnei Shomron to the north; Yaqir and Nofim to the south. Later on, settlement outposts were established: Alonei Shilo, El Matan, and Yair Farm. Outposts are colonies which are not authorised by the Israeli government, but often grow into settlements which are sanctioned by the government but illegal under international law.

The settlements have brought destruction to both the Palestinian people and the natural environment. “This month the settlers stole five of our goats,” says Rezeq when we meet him in April.

Settlements and outposts have discharged their waste water into the Wadi, polluting the springs and water supply for farmers. This forced the 50 Palestinian families who were living in the Wadi to move to Deir Istiya. According to B’Tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, outposts are still releasing waste water directly into the reserve and blockages in the sewage systems of Nofim and Yaqir also occasionally result in pollution of the stream.

Nature reserves in Palestine are not necessarily a positive development, in fact they can be an important tool in imposing apartheid conditions against Palestinians. The restrictions which stop Palestinians from building in nature reserves are not enforced against the Israeli settlements. “We have to recognise that for them it is not a nature reserve,” says Rezeq. “For them they can build everywhere.”

Rezeq is hopeful that once companies, like JCB, know what their machinery is being used for they may be motivated to do something about it, and prevent the Israeli state from using their equipment to destroy Palestinian houses.

The area was declared a ‘nature reserve’

“As activists, it’s our role to show the company that they [The army and the Israeli Civil Administration] are using the machines to demolish homes,” he says “Then I’m sure they will take the decision to boycott. When the company owners see what’s happening they will not co-operate with the state.”

Rezeq says that if JCB knows the truth about what its equipment is being used for, then the company must take steps to “end its tenders and contracts, and not have any economic relations with the state.”

For Rezeq, raising awareness of the companies which manufacture machines used in demolitions is part of the wider international Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

“I think the BDS movement has been successful. We can clearly see this, because the Israeli government sees it as an enemy.”

Rezeq says that he thinks BDS will have more success than “other types of activities against the occupation… Some people say that what is taken by force can be gained back by force, but I don’t believe in this way of resisting. I believe that it helps the occupation.

“When we talk about BDS we are talking about popular resistance, working in society. Campaigns against companies like Caterpillar or JCB are just a small part of this. We need strong support for BDS and for non-violence and the popular resistance. We are already working with international groups to put pressure on these companies, together we can succeed and find a solution.”

3 Comments

British firm JCB helps Israel commit war crimes | SRI LANKA · 1st October 2018 at 1:16 am

[…] February 2018: Israeli forces used a JCB machine to flatten the home of 58-year-old Rezeq Abu Nasser in the village of Deir Istiya, east of […]

British firm JCB helps israel (apartheid state) commit war crimes | Uprootedpalestinians's Blog · 2nd October 2018 at 9:14 am

[…] February 2018: Israeli forces used a JCB machine to flatten the home of 58-year-old Rezeq Abu Nasser in the village of Deir Istiya, east of […]

British firm JCB helps Israel commit war crimes – aladdinsmiraclelamp · 2nd October 2018 at 9:16 am

[…] February 2018: Israeli forces used a JCB machine to flatten the home of 58-year-old Rezeq Abu Nasser in the village of Deir Istiya, east of […]