By Tom Anderson & Therezia Cooper

During January 2013, Corporate Watch conducted interviews with Palestinians who work in the illegal Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley. Part one to three of our findings can be read here, here and here.

We met 44 year old Rashid* and 38 year old Zaid* in their hometown of Tammoun in the northern West Bank. They both work in the illegal Israeli settlement of Beqa’ot, a colony with 171 residents situated close to the Palestinian community of Al Hadidya in the Jordan Valley.

Tammoun is situated just outside the Jordan Valley. Like thousands of other Palestinian workers Zaid and Rashid travel into the Jordan Valley in search of work on a daily basis. To cross into the valley they have to pass through the Israeli military checkpoint at Tayasir or Al Hamra.

Rashid has worked in Beqa’ot since the early ’90s whereas Zaid worked in Israel until 5 years ago. Zaid tells us: “Now it is impossible for me to get a permit to work outside the West Bank.”

For Israeli companies, sourcing their goods from the settlements in the Jordan Valley allows them to circumvent workers rights and health and safety regulations. According to Zaid: “Inside Israel the workers have contracts and the conditions are better. This is because in Israel there are some controls on companies, unlike in the West Bank.”

Both men work all year round except for September-November when there is no work available. They have no contracts and tell us that none of their workmates do either. Their job is to plant grapes and tend to the vines, pruning them and spraying them with fertilisers and chemicals. At harvest time they cut and collect the grapes.

Grapevines in the settlement of Beqa’ot, photo taken by Corporate Watch, February 2013

Zaid and Rashid both work in the fields outside the boundaries of Beqa’ot. They do not have a permit to enter the settlement itself.

Paid below the minimum wage

Palestinian workers in Israeli settlements have been entitled to the Israeli minimum wage since an Israeli Supreme Court ruling in 2007 (see here). In 2010 Corporate Watch conducted over 40 interviews with settlement workers showing that Palestinians are consistently paid as little as half the minimum wage. These conditions remained largely unchanged when we returned in 2014.

The current hourly minimum wage is 23.12, NIS (New Israeli Shekels),the equivalent of 184.96 NIS for an eight hour working day, having risen from 20.70 NIS in 2009. However, for Palestinian workers on Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley these conditions seem an impossible dream.

Zaid and Rashid are employed directly by the settlers in Beqa’ot and speak to them directly to arrange their work. Both get paid 82 New Israeli Shekels (NIS), 18 of which goes towards daily transport.

They have no insurance provided by their employer. Rashid explains: “Last year one of the workers died, but the settlers did not help his family at all.

The men do not receive any paid holiday, even for religious holidays. This is despite the fact that an Israeli government website advises that workers are entitled to 14 days paid holiday and must receive a written contract and payslips from their employer (see here).

Both men are members of the General Palestinian Workers Union (GPWU). However, they are unable to represent workers in Beqa’ot or negotiate with their bosses. According to Rashid: “We organise trainings for agricultural workers but we are not recognised by the settlers, we do not receive any representation from Histradrut”.

Histradrut is the Israeli trade union organisation. Many campaigners for boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israeli apartheid have called for a boycott of the Histradrut because of its failure to represent Palestinian workers and its overt support of Israeli state policies.

For example, in 2010 the British University and College Union broke ties with the Histradrut; a UCU spokesperson said the Histradrut, “supported the Israeli assault on civilians in Gaza” and “did not deserve the name of a trade union”.

Companies sourcing produce from Beqa’ot

Mehadrin Tnuport boxes ready to be packed with grapes, photo taken by Corporate Watch in February 2013

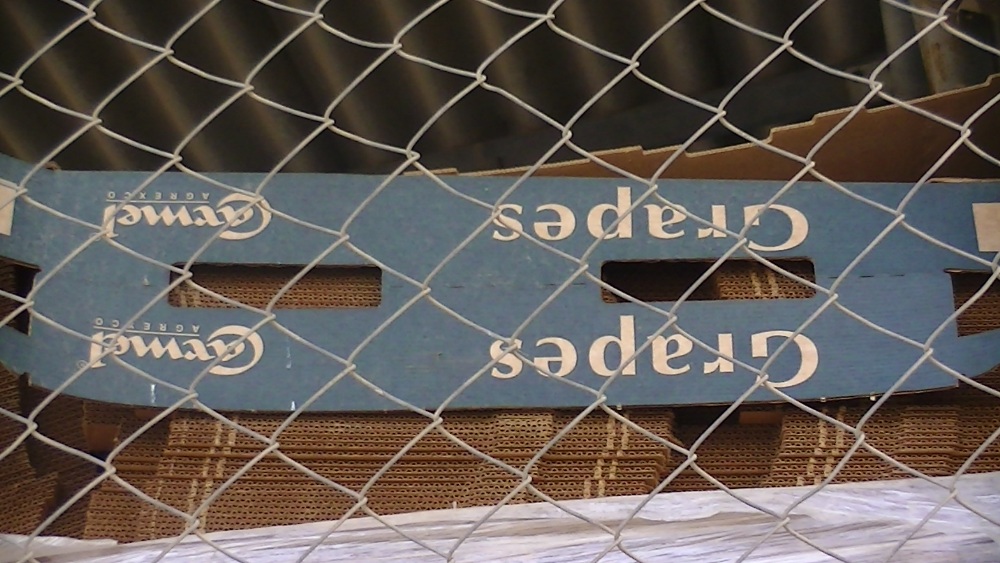

Carmel Agrexco boxes ready to be packed with grapes, photo taken by Corporate Watch in February 2013

STM boxes ready to be packed with grapes, photo taken by Corporate Watch in February 2013

Export label on a box in Beqa’ot stating that these grapes are shipped by Carmel agrexco, Photo taken in Febuary 2013 by Corporate Watch

Rashid tells us: “We label the grapes ‘Made in the Jordan Valley’ and mark them with the name and phone number of the Israeli settler.

“Each of the settler has his own packing house. When we harvest the grapes they are taken first of all to packing houses in Beqa’ot owned by individual settler, then transported to a central refrigeration unit owned by the Moshav [a Hebrew word for a cooperative farm]. Then a refrigeration truck takes them to be exported.”

The men tell us that the majority of the grapes they harvest are exported through Mehadrin.

Corporate Watch visited Beqa’Ot in February 2013 and photographed several packing houses displaying Mehadrin signage. Israeli company Mehadrin Tnuport Export (MTEX) is a part of the huge Mehadrin Group which owns a 50% of STM Agricultural Exports Ltd – another Israeli company dealing in vegetables. MTEX export around 70% of all their produce to outside Israel and are one of the largest suppliers for the Jaffa brand world wide. Sainsburys confirmed to Corporate Watch in August 2013 that the supermarket sourced fresh vegetables from Mehadrin. Mehadrin is also certified to supply fresh produce to Tesco (see here).

Corporate Watch also photographed boxes and export labels for Carmel Agrexco in Beqa’ot. Carmel Agrexco was the Israeli state owned fresh produce export company. In 2011 the company went into liquidation, due in part to the international boycott movement. The brand has since been bought by Gideon Bickel of Israeli firm Bickel Flowers and has been fighting to regain lost contracts.

Working for poverty wages on land stolen from their families

Rashid and Zaid refer to Beqa’ot by its Palestinian name, Libqya. Rashid tells us: “Before the occupation in 1967 Libqya was owned by Palestinians who used it for planting crops and raising animals. All of the families around here owned land in Libqya.

“I remember when my mother passed Libqya when I was young she told us how she used to play there with her brothers and sisters. Our family owned 70 dunums of land there. This reality is too painful. When I was older I tried to reach the land my mother told me about. But a settler told me I was forbidden to go there.”

‘We will get back our land’

Greenhouses in the settlement of Beqa’ot, photo taken by Corporate Watch in February 2013

Both men are supportive of the call for a boycott of Israeli agricultural companies. When it was pointed out that if the boycott was successful then their employers would not be able to pay them a wage any longer Zaid responded:

“We support the boycott even if we lose our work. We might lose our jobs but we will get back our land. We will be able to work without being treated as slaves.”

* Names have been changed at the authors’ discretion

0 Comments